Art and Fashion. A brief study of its historical relations.

“Architecture affected clothes, clothes modified anatomy”

Gerald Heard, 1924 [1]

In its history, Fashion keeps artistic references that undergo discredit as the advent of the industrial era organises society. When this modality of creation and human expression embraces, without so much resistance, the complex system of mass consumption of societies that end up leaving the artistic element in the background, as Gilde de Mello e Souza explains in her book, “The Spirit of Clothes” (1987).

However, despite the apparent distance between the Art and Fashion systems, the compositional elements of each can be analysed in a very similar way. Contrary to what is generally stated, the exchanges between the two are often, particularly during the twentieth century, evidenced by its construction and surface design.

Frédéric Godart takes another approach to the issue from what he understands as a specific social change. Continuous, non-cumulative and profound changes in society, different from Art and science that overlap with previous events, every six months or less, something new emerges in Fashion and is gradually incorporated by parts of society, changes that reverberate to music and customs.

Fashion, therefore, serves a social, functionalist structure linked to a clash of individualising and socialising desires. Its creators do not necessarily force some sense into their flow of new releases, which is understood nowadays as a trend that must be sensitive to its depletion and new demands of society for creation in this field.

Therefore, it is less important to evaluate the relationship between Art and Fashion just for its aesthetic characteristics. However, it seems more compelling to promote an analysis that inserts it in the oscillations of its social and temporal context in order to provide readings on people’s behaviour. The design of clothes reconfigures the body’s shape in a way more evidenced by the radicalism of visuality in the contemporary world.

Inside their studios, creators, either artists or designers, elaborate new pieces dealing with similar formal issues such as the balance of volumes, rhythms, lines and colours. The creation must be coherent with their project and appropriate to its multiple purposes.

When the approach considers the creative concept of the object of Art and Fashion, one realises that the exchanges are even more direct. Gerald Heard, in his text “Narcissus: an Anatomy of Clothes” (1924), says that the forms of Architecture of a period determine the forms and prints of the clothing of the same period. Referring directly to the aesthetics of Art Nouveau, the author states that

This circumstance is considered punctual and can be analysed at other historical moments. Examples of this approximation are evident in the relationship between Gothic ogive arches and the application of this form in the clothing of this Medieval period.

Alice de Bures, widow of Sir Guy Bryan, in widows’ dress

Brass Rubbing

1435 (made)

Confirmation from the Seven Sacraments

Tapestry

1470-1475 (made)

James Laver takes it further and understands that, over time, Fashion confirms status as a forerunner of taste that is then translated into decoration and architecture [2]. The author argues that it is initially in the clothes that functionalism proves necessary. This functional circumstance is applied to the use of new materials for the making of furniture and profound innovations in architecture seen particularly after the 1930s.

Nevertheless, it is possible to see that both agree on a close exchange in the creative, technical and functional fields between areas. Many authors understand this symbiosis by what is determined as Zeitgeist [3], the “spirit of the time”, studied by German Romanticism and widespread throughout the twentieth century in the most varied domains of human creation.

“The spirit of the time is nothing but the spirit of those in power.”

Goethe[4]

In Brazil, it is possible to classify the Zeitgeist from a sensible confluence between that proposed by the German philosopher Goethe and the concepts presented in Helio Oiticica’s multi-linguistic production, particularly in his text “General scheme of the New Objectivity”[5] of 1967. In his text, the artist-author elects characteristics for the Art produced at that time, such as Constructivist intention, political/social position, spectator participation, and collectivity. Thus, the elements used by Hélio Oiticica in artistic and textual production influence as much the creators of other areas as the clothing designers of that period and echo up to the present day, as they fit into the Brazilian social context. Oiticica’s multi-disciplinary attitude establishes a national identity by dialoguing directly with so many layers of society, thereby generating a new movement in the cultural scene.

The complexity of the significance exchanges adopted by Art and Fashion in this period propose interactions between high and low culture, as it happens with Helio Oiticica’s “Parangolés”. The colours, the samba and the people are evoked to activate the work in front of the Museum of Modern Art Rio de Janeiro – MAM Rio.

P 2 Parangolé flag 1 (1964) in the centre of the photo, at the opening of the exhibition Opinião 65, outside MAM Rio, in 1965.

Photo Desdémone Bardin

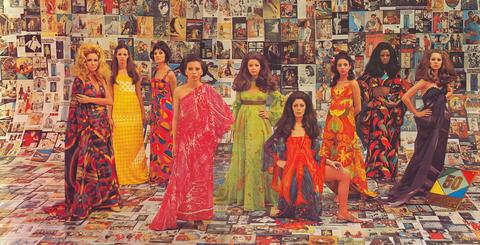

In Brazil during the 1960s, an example of the close relationship between artists such as Alfredo Volpi, Manabu Mabe, Tomie Othake, and Iberê Camargo, among others, and designers like Dener Pamplona, Alceu Penna e Ugo Castellana in collaboration for the runaway shows promoted by the multinational Rhodia.

At that moment, the connection between what is produced in Brazil and what is typically Brazilian is established. Furthermore, local and global issues are necessarily addressed to understand the apparel produced during this period in the country. Elements related to international haute couture, in this case, French, were associated and often limited to Brazilian stones, feathers and leather.

Fenit (National Textile Industry Fair) became a cultural event, promoting not only the company’s fashion shows but also performances by the great stars of Brazilian Popular Music and Bossa Nova, such as Gal Costa, Caetano Veloso, Gilberto Gil, and Nara Leão.

Bibliographic Reference

- Gilda de Mello e Souza, O Espírito das Roupas, 2005, Pág. 34

- MELLO e SOUZA, G. Op cit.

- As defined in the Dictionary of Philosophy tome II by J Ferrater Mora, its literal translation of German is “spirit of the time” whose circulation is mainly due to Hegel, and which was adopted and elaborated by several “romantic” authors (…) could be called “the profile” of an epoch. MORA, J. F. Dicionário Y PT O, 2001, Pag 885

- RESENDE, José and CORREA, Patrícia Leal. José Resende. 2004. Page 185

- Oiticica, Helio. General scheme of the New Objectivity. In: FERREIRA, G and COTRIN, C. (org) Artist Writings. 2009, Pag154 – 168

The article continues in the next post: The idea of a wearable sculpture >